OUR THOUGHTSTechnology

Team Topologies – team interaction mapping

Posted by The HYPR Team, Luke McManus . Oct 09.25

Organisations worldwide struggle with the same fundamental challenge – translating strategic objectives into customer value while maintaining team effectiveness and individual wellbeing.

The gap between organisational charts and actual value delivery remains, creating friction that manifests as overloaded individuals and teams, excessive coordination overhead and delayed delivery cycles.

Team Topologies offers a framework for addressing these challenges, but many organisations stumble when moving from theoretical understanding to practical application. Rather than artificially forcing existing team structures into future topologies, this article outlines how to start with your current state and make a deliberate evolution toward topologies that improve work and information flow.

The approach reflects the need for more continuous change and leads to smaller, more frequent adjustments over time, which become easier with practice.

Recognising signals for organisational change

Effective change begins with recognising symptoms that indicate structural misalignment. Value delivery slowing down represents the most visible signal, but the underlying causes often remain hidden in the friction of organisational work and information flows.

Individuals experiencing cognitive overload struggle to maintain quality while meeting delivery expectations. Dependencies across multiple domains and technologies fragment attention and reduce effectiveness. Large teams often struggle to communicate effectively. Poor alignment from strategy to value leads to wasted effort and poor customer feedback.

When customer-facing teams undertake a significant amount of heavy lifting (such as infrastructure and environment management), it leads to slower progress. Unclear roles and responsibilities can lead to conflict or tension. These symptoms rarely appear in isolation. Once friction appears, it often compounds and causes other symptoms, making it harder to diagnose.

Collaboration and coordination take effort and time. While collaboration is often touted as a positive goal, excessive or sustained collaboration incurs specific costs, particularly related to communication and coordination. Sometimes collaboration indicates improvement opportunities. For example, excessive collaboration around a poor release process may indicate the need for improved technical practices around deployment and environment management.

Organisational communication channels optimised for reporting rather than value delivery can also obscure or cause friction. When teams require hierarchical navigation to make simple decisions, the focus shifts from customer outcomes to internal process compliance.

The most expensive signal involves dependencies and handoffs between teams. Each handoff represents not just delay, but context loss that compounds over time. Teams downstream from handoffs begin work with incomplete understanding, reduced ownership and diminished agency. The human cost extends beyond efficiency metrics to include disengagement and decreased job satisfaction.

Understanding team types and interaction modes

Stream-aligned teams form the foundation of effective organisational design by aligning closely with genuine user or customer value. These teams require comprehensive capabilities to deliver value independently, but achieving this autonomy often demands support from other team types.

Platform teams reduce cognitive load by providing compelling internal services that accelerate delivery across multiple stream-aligned teams. Rather than forcing every team to master infrastructure provisioning or environment management, platform teams create self-service capabilities that enable focused value delivery. This necessitates thinking about platforms as products with internal customers, requiring the same product management discipline applied to external offerings.

Complicated sub-system teams handle specialised domains that would otherwise overwhelm stream-aligned teams. These may involve complex algorithms, regulatory compliance or technical domains that require deep expertise. The decision to create such teams should be driven by cognitive load considerations rather than organisational convenience.

Enabling teams facilitate change by helping stream-aligned teams adopt new technologies, tools and practices. They operate across organisational boundaries, identifying common patterns and emerging needs. Their temporary nature distinguishes them from long-lived stable teams, as their success is measured by the independence they create for other teams as they learn new skills.

The evolution of team interactions

Team interactions evolve through predictable patterns that organisations can leverage for improvement. Collaboration represents a necessary but expensive interaction mode that should be time-boxed and outcome-focused. The goal of collaboration is to solve specific problems or acquire new capabilities, rather than creating permanent coordination overhead.

The evolution typically progresses from collaboration to facilitation and then to self-service consumption. When teams collaborate on novel problems, successful solutions often become candidates for service offerings. Rather than throwing solutions over organisational walls, facilitation helps consuming teams understand and adopt new capabilities safely.

X-as-a-service represents the most efficient interaction mode by eliminating human-to-human coordination for routine consumption. Teams can access documented APIs and services without interrupting other teams or prioritising work in their backlogs. This vending-machine-style self-service capability scales consumption while reducing provider burden.

This pattern of evolution applies broadly, beyond technology services. Business capabilities, approval processes and decision-making authorities can all evolve toward self-service models that reduce coordination overhead while maintaining necessary controls.

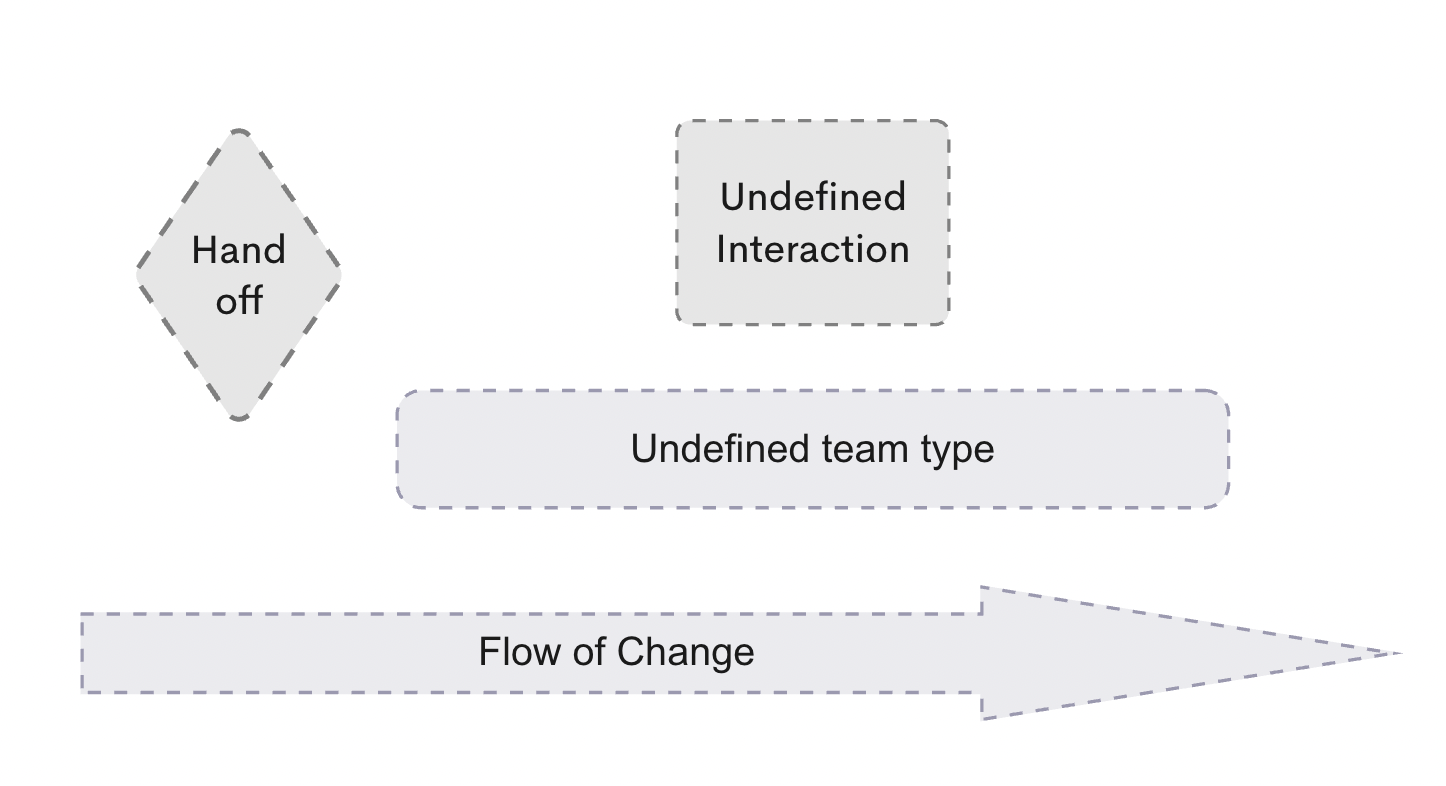

The most valuable concept when starting to model team interactions involves the undefined team type and interaction mode. Rather than forcing existing structures into predefined patterns, undefined designations acknowledge current reality while creating space for improvement conversations.

Teams that cannot be clearly categorised into stream-aligned, platform, enabling or complicated sub-system teams signal opportunities for change. Their undefined status prompts questions about purpose, capabilities and interaction patterns that might otherwise remain unexamined.

Similarly, interactions that do not fit collaboration, facilitation or X-as-a-service patterns deserve undefined classification. This honest assessment reduces confusion and creates curiosity, conversation and possibilities.

Starting with undefined designations eliminates the temptation to retrofit existing structures into idealised topologies. Organisations can acknowledge current constraints while working toward improved patterns through deliberate evolution.

Practical mapping techniques

Team interaction modelling is a visual representation that captures the current state and flow characteristics. The process begins by mapping the flow of change from initial concept through customer delivery, identifying all teams and handoffs involved.

Each team receives an initial classification as undefined until evidence supports a specific team type designation. Interaction patterns similarly begin as undefined until they demonstrate clear collaboration, facilitation or X-as-a-service characteristics. As mentioned above, it’s the improvement conversations and discussions that are generated by visualising the flow of value that are some of the most important outcomes of the mapping exercise.

The mapping process reveals patterns that are not visible through organisational charts, financial reports or process documentation (typical management views of the world?). Handoffs that appear minor in isolation often represent significant bottlenecks when viewed across entire value streams. The more handoffs that exist inside a value stream, the higher the cost of coordination and the slower the delivery of value becomes?

Moving towards capability-based thinking

Effective team design requires shifting from a people-based to a capability-based approach. Individuals possess multiple capabilities and capabilities can be distributed across multiple team members. This perspective enables a more flexible team composition and a clearer definition of responsibilities.

Some capabilities can be learned and adopted by all team members. For example, a working knowledge of customer empathy goes a long way for anyone working in a customer-facing, stream-aligned team.

Capabilities encompass both technical skills and decision-making authorities. Teams require not only the ability to perform work, but also the authority to make necessary decisions without external escalation. This autonomy reduces coordination overhead while improving response times – important as the speed of the decision often impacts its value.

The capability lens also clarifies platform and service design decisions. Rather than asking which team should provide specific services, organisations can ask which capabilities need to be accessible and how they can be delivered most effectively.

As products mature, a single team can’t do everything and remain efficient. For a team to remain small and nimble, some of the ‘heavy lifting’ may be offloaded to platform teams.

Not many teams work in isolation either; almost all teams are part of a team of teams (or value stream). The capability lens can also be applied to a team of teams. Aligned to customer value – with all the necessary skills and capabilities to deliver end-to-end value.

Continuous evolution and adaptation

It’s time to move away from static organisational designs and large re-orgs. Static infrequent organisational designs fail to respond to changing conditions and become increasingly misaligned over time, requiring ever larger and more disruptive adjustments. Team structures and interaction patterns must evolve continuously as technology, market conditions and organisational context change.

Cross-organisational perspectives play crucial roles in sensing emerging needs and identifying optimisation opportunities. Understanding how work and information flow from concept to cash helps find friction where team topology changes are required.

The evolution process requires regular assessment and adjustment rather than major reorganisation events. Small, frequent changes prove more manageable and less disruptive than large structural overhauls.

Organisations that embrace continuous evolution develop organisational resilience and adaptability that serve them well in changing environments. The ability to sense and respond to structural misalignment becomes a habit.

Leading team interaction mapping

Successful team interaction mapping requires leadership commitment to honest assessment and incremental and continuous change. Organisations should resist the temptation to declare victory by mapping current structures to idealised patterns without addressing underlying issues.

The process works best when conducted collaboratively with affected teams rather than imposed from above. Teams understand their current constraints and interaction patterns better than external observers, making their input essential for accurate mapping.

Change initiatives should focus on removing the most expensive handoffs and dependencies first. Quick wins build momentum for larger structural changes, while demonstrating the value of the approach.

Measurement and feedback mechanisms help organisations track progress and identify new opportunities for optimisation. The goal involves improving flow characteristics and team effectiveness, rather than achieving perfect adherence to theoretical patterns.

Team interaction mapping provides practical tools for organisational improvement, but success depends on honest assessment, incremental change and continuous adaptation. Organisations that embrace these principles can create more effective structures that better serve customers and team members.

The HYPR Team

HYPR is made up of a team of curious empaths with a mission that includes to teach and learn with the confidence to make a difference and create moments for others.

More

Ideas

our thoughts

Data and analytics: are you asking the right questions?

Posted by Brian Lambert . Feb 09.26

The conversation around Artificial Intelligence in enterprise settings often focuses on the technology itself – the models, capabilities, impressive demonstrations. However, the real question organisations should be asking is not whether AI is powerful, but whether they are prepared to harness that power effectively.

> Readour thoughts

The future of voice intelligence

Posted by Sam Ziegler . Feb 01.26

The intersection of Artificial Intelligence and voice technology has opened fascinating possibilities for understanding human characteristics through audio alone. When we hear someone speak on the phone, we naturally form impressions about their age, gender and other attributes based solely on their voice.

> Readour thoughts

Is AI the golden age for technologists?

Posted by The HYPR Team . Oct 27.25

The technology landscape is experiencing a profound change that extends beyond the capabilities of Artificial Intelligence tools. We’re witnessing a fundamental shift in how people engage with technology, build software and think about their careers in the digital space. This shift raises a compelling question... Are we entering a golden age for technologists?

> Readour thoughts

The IT fossil record: layers of architectural evolution

Posted by The HYPR Team . Oct 20.25

The metaphor of an IT fossil record captures something interesting about how architectural thinking has evolved over decades. Like geological strata, each architectural era has left its mark, with some layers proving more durable than others. The question remains whether we’ve reached bedrock or continue to build on shifting sands.

> Readour thoughts

OKR mythbusters: debunking common misconceptions about objectives and key results

Posted by The HYPR Team . Oct 13.25

The rise of Objectives and Key Results has been nothing short of meteoric over the past 15 years. What started as a Silicon Valley method used by a select group of tech companies has evolved into a global business framework adopted by organisations across every industry.

> Read